THREE WHEELS ON MY WAGON

By George Duckett

Ever since I was quite young, I wanted to work in wood. A lifetime in engineering, working in a very precise environment, gave me many metalworking skills, and it was only in my retirement that I became deeply involved with a variety of woodwork.

One of these was wood turning and another, satisfying a long term ambition, was the construction of models of horse drawn vehicles.

Many people to whom I spoke at shows and exhibitions plus those from whom I sought advice, seemed to think that miniature wheel wrighting was the most difficult part of this hobby. I tried to find propriety wheels to fit and even managed to obtain the odd wheel kit but none of them came up to my expectations. Eventually I came across the Hobby’s Plan (No. 1514P ) which, initially seemed too complex & beyond my capabilities. However, when I actually sat down and attempted to follow the diagrams and construct the wheel, I found it a great deal easier that I had imagined.

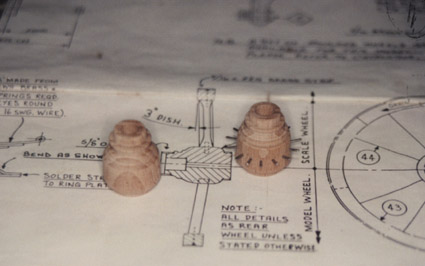

First of all, you have to consider that cart and wagon wheels have three main parts; the hub (referred to as the "nave" in full sized terms), the spokes and the rim. The hub is, of course, round, and if you can find suitable sized wooden dowel from which to make it, then do so, for it saves time and effort. Otherwise it can be made from square section timber.

Due to the circular nature of wheels, it is really a requirement of their manufacture that you have tools to work "in the round!" Obviously a lathe is the best tool to use, but I have made wheels on home made jigs, using either an electric drill as the driving source, or an old washing machine motor driving a ball raced spindle, both of which I picked up cheap at a model engineering show.

The Middle Bit.

Regarding the hub, it needs ultimately to rotate on an axle so an axle bearing needs to be fitted. Whilst most full sized wheels rotate on a tapered axle, most models for simplicity use a parallel steel rod, which in turn simplifies the bearing, to the point where standard "model shop" brass tubing will suffice.

Using a pillar drill, or a pistol drill in a stand, drill through the centre of the hub and push fit the brass tube into the hole. The tube should only go some 3/4 of the way through the hole, and should protrude from the other end of the hub by about an inch.

When you are satisfied with this, glue the tube into the hub with slow setting epoxy. The extending tube now makes the mandrel to allow you to turn the hub to the required profile and to bore the outer end of the hub, to take the fixing pin.

Various hub profiles can be found, dependant upon the type of wheel, but they can all be carved and sanded from the spinning blank, using only hand tools and sand paper.

Remember to take off a little wood at a time, constantly stopping to measure and to check the profile. Measurement is best done with a pair of callipers and profiles can be checked with the aid of a template cut from card.

Front and back of the hub are ringed with steel. (Known as nave bonds!)

If you are very lucky, you might find thin walled metal tubing of the right diameter to fit. However, in many cases you will not, (particularly as the inner and outer bonds are usually of different sizes!) and thin strip metal has to be used. I use the metal strapping that secure some loads to their pallets which can frequently be found, discarded in builders skips. This steel strapping is of about "scale" thickness and can be cut down to narrow strips with tin shears, or heavy domestic scissors.

(Do not use best dressmaking scissors)

Curving the strip to fit is best done by rolling enough strip for two or more wheels, around a rod or dowel, a little bit smaller than the finished diameter. It can then be "sprung" over the hub and trimmed to fit. Again, when totally satisfied with the fit, epoxy the rings in place, securing them with rubber bands, or masking tape, until the epoxy is fully cured.

When putting the hub back into your turning device an emery cloth can be used to clean up the face and the outer edges of the bonds, producing a most professional appearance.

The only remaining job here, is to drill the holes (mortices!), for the spoke ends.

The number of spokes fitted to a wheel will vary, dependant upon the size and the style of the wheel, and may be all in one plane, or staggered. For most modelling situations, single plane spokes are more than adequate.

Two points need to be brought to one’s attention at this juncture.

First, and most obviously, is the fact that wheels are "dished". In other words the spokes are not at right angles to the axle but slope out in such a manner as to allow the axle to slope down, yet still allow the bottom of the rim to be at right angles to the road. Axle angle, and subsequent dishing angles vary too, and are usually somewhere in the region of two to five degrees.

The second point is equally obvious, in as much as the spokes must be evenly spaced around the circumference of the hub. (There are exceptions to this rule, but they fall outside of the scope of this feature!)

Therefore we have to make up some sort of jig to hold the drill at the dish angle when drilling the spoke holes and we have to make up another jig to ensure that when rotating the hub for the next hole, it moves at exactly the right number of degrees.

Both of these jigs can be made from scrap plywood, metal tube, etc. and if carefully measured and fitted, will provide adequate accuracy.

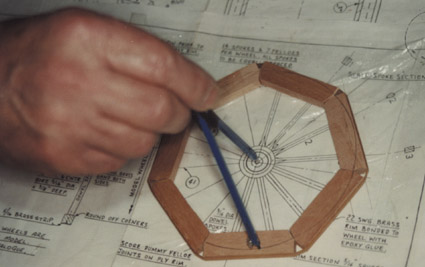

The Outside Bit

The rim of the wheel is made from several sections of wood, (Proper name, "felloes"!!), suitably joined together. Two spokes fit to each felloe, so the number of felloes is predetermined. Draw out the wheel to full size on paper, marking the inner and outer diameters of the rim. Then draw on the dividing lines that will show where the felloes join. The angle of these lines depends upon the number of spokes and is really just schoolboy geometry. (For those of us who flunked maths, the angle for 10 spokes is 72 degrees, 12 spokes is 60 degrees, and for 14 spokes it is 51 1/2 degrees.)

From this it is easy to see the angle that the strip wood must be cut, in order that the felloes join correctly. Once again, a simple wooden jig will help to cut each felloe to the same angle. When stripping down the timber to make the felloes, it is worth making them a bit fatter than is actually needed. This will result in having to remove more timber during the finishing but allows better handling during this stage.

Laying a cut felloe onto the drawing will make this perfectly clear.

When you are perfectly satisfied that the polygon you now have is equal all the way round, the felloes may be stuck together with proprietary wood glue and clamped up until dry.

On full sized wheels, felloes are actually doweled and glued together and this can be done, too, on models and is immensely satisfying. However, it is not a necessity in most model scales, for the strength of today's wood glues is more than adequate!

When all is dry, lay the assembled rim over the drawing and , using a pair of compasses, draw on the inner and outer circumferences of the rim.

It now requires that the rim be trimmed to these lines. There is some debate as to whether to do the inside or the outside first. On balance, I think that doing the inside first is probably best. Once more, make up a simple wooden jig, or "faceplate", to give it it's proper title, to which you can attach the rim. Small brads can be used to secure the rim to the turning jig, if they are used outside of the finished diameter.

Alternatively, small pieces of wood may be used as spacers and the rim clamped to the jigging plate.

Spinning the rim in lathe, or drill, gently carve away the surplus wood, working from the inside, up to the inner pencil line. Again, "little and often", is the name of the game.

When the inner is to your satisfaction, reposition the fixing clamps and repeat the job on the outside edge, once more, removing only a little wood at a time. Constantly check the diameter.

Wheel rims, like hubs, have an outer band of metal, or "tyre", and as before, this can be fabricated from strip steel, curved and fitted.

Being somewhat longer than the hub strips, there is some mileage in drilling small holes, (say around 1/32" ), at each end of the strip and a couple more spaced around the circumference. This allows small nails to be used to hold the tyre in place while the glue dries. These nails can be removed, or simply clipped off when the glue is hard and the rim can be refitted to the turning plate, so that the tyre may be smoothed and polished with emery cloth.

The Bits in the Middle!

Many model wheels use dowel for spokes and, in smaller scales, this looks quite satisfactory. However in bigger scale models, it really needs spokes of proper cross section to make things "look right"!

Most wagon wheels have rectangular section spokes and strip wood should be cut and prepared for this job. Use the scale drawing to determine the width and thickness of the spoke blanks but cut them at least 1/2" over length. Once more, it is time to make up yet another jig, this time to allow every spoke to have the correct dishing angle cut at its root. Also at the root, an extension needs to be left sticking out, to a tad less than the depth of the holes, drilled to receive the spokes, in the hub. These protruding ends now need to be sanded round to fit into the holes.

It takes quite a long time to get all the spokes to the right fit in the hub but it must be done, correctly, before the spokes have any further work done on them. When satisfied, remove the spokes from the hub and carve, or sand, in the chamfers. Use a card template to check that each chamfer is the same.

Putting it all together!

One final jig is needed here. A piece of plywood, or MDF, forms the base and a steel bolt fitted upright, in it's centre, is the bearing for the hub. A ring of plywood is now cut to support the spokes, some 1/4" or so in from their ends. The thickness of this ring must be such that the correct dish angle is formed when the spokes are positioned in the hub and the jig. Thin washers may be used beneath the hub to achieve the final angle. Radial slots may be made in the top face of the ring at the correct spacing to locate the spokes, or two small brads can be knocked into the ring, either side of each spoke.

The spokes may now be glued to the hub and left to dry. It remains only to trim off the ends of each spoke to the same length and to fit the rim.

The assembly jig may be clamped to the bench or a rotary sander, turning the hub and spokes assembly gently past the sanding disc, and finishing to an equal and exact length. Alternatively the spoke ends can be sanded by hand but with care. Stop and check repeatedly, for this is not the time to sand one spoke too short!!

Finally, drop the rim over the spokes to form the finished wheel. The rim should be a firm push fit over the spokes, without any undue force being needed and all of the spokes should just touch the inner face of the rim.

Remove the rim and lay it over the drawing, marking in pencil, the points on the inside of each felloe, where each spoke fits. (Remember, two spokes to a felloe, and spokes do not go on the joints!!)

Now refit the rim to the spokes with white wood glue, carefully wiping off any excess with a damp cloth.

Prop up the rim around its circumference with scrap blocks of wood, to ensure that the rim is at constant height from the base of the jig, all the way around, and that the spokes fit exactly in the centre of the rim at each joint.

Now leave overnight to dry and start the second wheel.

If, like me, you tend to make duplicate parts, as you go along, the second matching wheel will consume a great deal less time, as most of the parts are already to hand.

Please do make sure that you follow the old adage, "Measure twice - cut once!", and ensure that wheels really are "matched pairs!"